COVID-19

The UK is hosting COP26, an annual United Nations climate change summit, in the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, posing both a local and global public health risk (as of the middle of October, the UK was recording 50,000 new cases per day).

It didn’t have to be this way. The inability for COP26 to be held safely is a direct result of the “vaccine apartheid” which countries like the UK, US, EU, Norway and Switzerland have imposed by taking positions against a World Trade Organisation patent waiver on COVID-19 vaccines and refusing to support technology transfer or manufacturing programs that would enable vaccine access in the Global South.

Delegates from developing country governments as well as civil society observers (who as well play an essential role in disseminating information, acting as a watchdog, and providing critical support to developing country governments) have been raising logistical, health and safety related questions with the UK Presidency for months. However guidance on issues such as COVID vaccines, quarantine periods and costs has often been insufficient, unclear, or too late. Half-measures to address questions of equitable access, such as waiving standard quarantine periods, do nothing to solve the underlying vaccine equity issues. The consequence is that many developing country governments and frontline communities are effectively being prevented from attending the summit. While every COP is exclusive and inequitable to a degree, COP26 is so exclusionary that it risks being seen as completely illegitimate and has diplomats talking about a collapse of the talks. As a result, a large swathe of civil society groups who normally follow and participate in the talks issued an unprecedented call for talks to be delayed again.

Rule Britannia

Hosting COP26 is a major PR opportunity for the UK government which seeks to appear as a “world leader” post-Brexit. The order from the top of the UK government to event planners was therefore to only plan for an in-person COP in Glasgow this November rather than consider calls to delay the event for a second time. This is in keeping with the UK government’s negligent response to the COVID pandemic, and with its attitude more generally: the short-term objectives of the ruling Convervative Party are put before other considerations like public health.

The UK vision for COP26 is primarily concerned with securing a positive image for itself rather than securing the best possible outcome from the negotiations. The main prong of the UK strategy is to corral countries into “following the lead” of the UK and announce a net zero 2050 target – something which is deeply inequitable and which does not meaningfully contribute to the reductions necessary to meet the Paris Agreement global temperature goal of limiting warming to 1.5C. Membership of this “net zero club” will be used as a benchmark for whether a country is a “leader” and those countries who do not join will be labelled “laggards” in much the same way the US-led “high ambition coalition” ran interference during Paris COP21.

The UK is also keen to land headlines on the “end of coal” and on its domestic policies related to vehicles (specifically the phase out of the sale of diesel cars) as well as announcements related to deforestation/afforestation and, crucially, has called on other countries to make increased pledges toward climate finance. The “coal, cars, canopy and cash” announcements will be used to label COP26 as a success. This will be a smokescreen. In reality, for any COP to succeed, countries must put people and the planet before profit by committing to a global plan for a justice transition, uprooting the systems of injustice that have created these crises to guarantee everyone the right to live with dignity in harmony with our planet. A more accurate measure of progress (rather than “success”) at COP26 is outlined in the box below.

| Indicators of progress at COP26 Rich countries pledge real zero 2030 targets with real plans – in line with fair shares for 1.5C – rather than the delay and greenwash of “net zero” 2050 targets. Countries define a process to measure progress towards the Global Goal on Adaptation and ensure adequate financial and technology support is available. Rich countries pledge to cease public subsidies for fossil fuels and instead scale up the levels of new and additional public finance (not debt creating loans nor market mechanisms) in line with the trillions of dollars developing countries need. Rich countries agree to provide additional public finance to support those bearing the brunt of losses and damages from climate breakdown today to help them recover and rebuild their lives. Countries abandon the false solution of offsetting and carbon markets and make a serious effort to advance real solutions via non-market cooperative approaches. Countries commit to develop a global plan for a rapid justice transition away from fossil fuels and other extractive, large-scale and corporate controlled false solutions, whilst tackling inequality and prioritising sufficiency and well being. |

The rocky road

to Glasgow

Due to deep divisions and disagreements at COP25 in Madrid in December 2019, many agenda items did not reach any conclusion and so, according to the (draft) UNFCCC Rules of Procedure, had to be automatically taken up at the next session. However, due to COVID-19, the next session could not take place in 2020 as scheduled, nor could COP26 which was delayed from November 2020 to November 2021. Parties were unable to meet physically and so instead met in an “informal” virtual format from 31 May – 17 June 2021. These meetings of the permanent “subsidiary bodies” to the Convention (the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) and the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technical Advice (SBSTA)) were meant to advance work ahead of COP26, but because of their virtual format were not allowed to produce draft decisions or negotiating text for COP26. Instead, they could only produce “informal notes” which do not have any status and are not supposed to be the basis for textual negotiations going forward.

These meetings were marred with all manner of technical and logistical issues from connectivity, to poor quality audio, to time-zone differences which all negatively impacted the talks. Some developing countries were unable to join due to power cuts, reinforcing their view that virtual meetings are not conducive to highly technical discussions. The session also saw many of the same old tensions emerge on each of the agenda items and in general, including a perception among developing countries that the issues were taken up in an imbalanced way, with topics such as finance, adaptation and loss and damage dealt with only superficially and/or pushed to Glasgow or taken up by the COP presidencies’ virtual processes.

Big issues at COP26

The issues being debated in the UNFCCC are recurring and best seen in the context of a long-term struggle between the Global North and Global South over who should take responsibility for tackling climate change and its impacts, which plays out at political levels as well as across all the technical negotiating items.

Limiting temperature rise to under 1.5C

In their 2018 Special Report on 1.5C, the IPCC said that global emissions must immediately start decreasing by 7.6% annually in order to have any chance of limiting temperature rise to 1.5C. Global emissions would need to be cut by a total of 50% by 2030, and continue their downward trajectory towards real zero (rather than “net zero”) . However by the UNFCCC’s own estimate, the countries’ current “Nationally Determined Contributions” would, if met, only result in a total of 12% reductions by 2030 and would see the world warm a devastating 2.7C by 2100. For a 66% chance of staying below 1.5C, total cumulative CO2 emissions must not exceed 230 gigatons. This is about five years of current emissions.

The NDCs therefore need to be drastically improved, with each country taking on its “fair share” of the collective effort, according to their “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” as stated in the Convention and the Paris Agreement. However, for developing countries, that extra effort is conditional on finance and technology being made available to them. Article 4.7 of the UNFCCC states that “The extent to which developing country Parties will effectively implement their commitments under the Convention will depend on the effective implementation by developed country Parties of their commitments under the Convention related to financial resources and transfer of technology and will take fully into account that economic and social development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of the developing country Parties.” Which is why it is essential that COP26 secures a positive outcome on climate finance (more below).

However, with even the UK as COP26 host seriously lagging behind in climate policy and nowhere near close to taking on its fair share of climate action, there is little incentive for other countries to ramp up their efforts. The signs are not good for staying below 1.5C. While Donald Trump may no longer be the President, the United States has not radically changed its longstanding approach to international climate change negotiations. Though the Biden administration may have doubled the US’ previous 2030 target, this is still a long way off its fair share. Actually, the US and UK are instead planning to pump out even more carbon into the atmosphere by increasing their production of fossil fuels. For precisely this reason, we can expect them to deflect attention away from their inadequate climate policies and onto the climate policies of China and India at COP26.

Because it was obvious even in 2015 that the NDCs were inadequate, the Paris Agreement established a mechanism for all countries to raise their level of ambition, known as the “Global Stocktake”. The first stock take is scheduled to commence post-COP26 and conclude in 2023, and will be based on the best available science and the principle of equity. In June, discussions led to a “non-paper” which includes a set of “guiding questions” for the Global Stocktake concerning topics such as past and present trends of greenhouse gas emissions, financial barriers facing vulnerable countries, and loss and damage. Countries have already agreed to include input from non-state actors.

Adapting to climate change

Rich countries have utterly failed to limit their pollution (despite knowing for decades the negative effects it causes) while also failing to support poor countries in developing in a clean and pro-people manner instead of with fossil fuels. As a result, the world is already 1.1C warmer than a couple of hundred years ago. While efforts to cut carbon pollution must be pursued vigorously, the reality is that societies have to adapt as best they can to the warming that has already occurred, something the UNFCCC recognises and which is discussed under the broad theme of adaptation.

The United Nations Adaptation Gap report estimates that the annual cost of adaptation in developing countries could reach $140-300bn by 2030. However, the OECD estimates that climate finance in 2019 totalled $79.6 billion, of which just $20.1 billion was earmarked for adaptation. In another report by Oxfam, it was found that 80% of all reported public climate finance in 2017 and 2018 was not provided in the form of grants – but mostly as loans – and only 25% of funding was spent helping countries adapt to the impacts of the climate crisis.

The most recent round of meetings in June covered some individual agenda items dealing with adaptation, such as the review of the Adaptation Fund, matters relating to Least Developed Countries, and the Nairobi Work Programme on impacts, vulnerability, and adaptation. While individual agenda items can be useful it is necessary to provide coherence over the broad matters of adaptation and work towards substantive outcomes at COP26.

One such outcome would be to put into action the Global Goal on Adaptation, by defining the Goal and a process to measure progress towards it. Developed countries – who want Nationally Determined Contributions to solely focus on mitigation, and leave adaptation, losses and damages and support for developing countries out – are opposed to formalizing a Goal. Agreeing on such a common goal however would allow evaluation of progress globally that should be defined both by the people and communities who are affected by climate change and by national data, and the Goal should be integrated into national policy frameworks in a way that makes sense given the context. However, in order to meet the Goal countries will need additional finance, capacity and technology support. COP26 should encourage pledges towards this.

Addressing and repairing climate impacts

Because rich countries have not only failed to cut their own pollution, but have also failed to help vulnerable countries and people adapt to climate change, we must now face up to the environmental, economic, social, cultural and impacts from climate change to which we can’t adapt. This is what policy-makers and experts refer to as “loss and damage”. Small island nations first raised the alarm back in 1991, but were fobbed off with insurance schemes. Nowadays insurance providers won’t cover for many of the effects of climate change as they have become too frequent or too certain. So while the UNFCCC has agreed that rich countries should provide climate finance for adaptation and mitigation, vulnerable countries are fighting for support for those recovering from climate disasters and slow-onset impacts.

At COP19 in Poland, poor countries and climate justice groups successfully fought to create an international mechanism for loss and damage. However, the rich countries did not allow Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) to work on its mandate of “action and support”, as a result limited progress was made on the critical issue of facilitating financial support to poor countries so that they can recover from the climate impacts.

While rich countries are also being hit by the climate disasters, they have resources to help their citizens deal with the impacts and rebuild their lives. But, when it comes to supporting developing countries, rich nations have sought to keep the entire issue of loss and damage relegated to a mere technical matter.

The projected economic cost of loss and damage by 2030 is estimated to be between $290 and $580 billion in developing countries alone. COP26 must decide to provide additional, sufficient and needs-based Loss and Damage finance, on the basis of equity, historical responsibility and the polluters pays principle, and must also establish a process to identify the scale of funding needed to address Loss and Damage as well as suitable mechanisms to deliver the finance to developing countries. The outcome must then be presented next year at COP27 in Egypt to start delivering Loss and Damage finance.

In Glasgow, countries will also discuss how to operationalise the Santiago Network for Loss and Damage (SNLD), established at COP25, with a decision on its form, functions, budget, and a process for its ongoing development. The SNLD is the first step in establishing the implementation arm of the Warsaw International Mechanism. A comprehensive decision and new and additional funding needs to be put in place at COP26 to make the network operational.

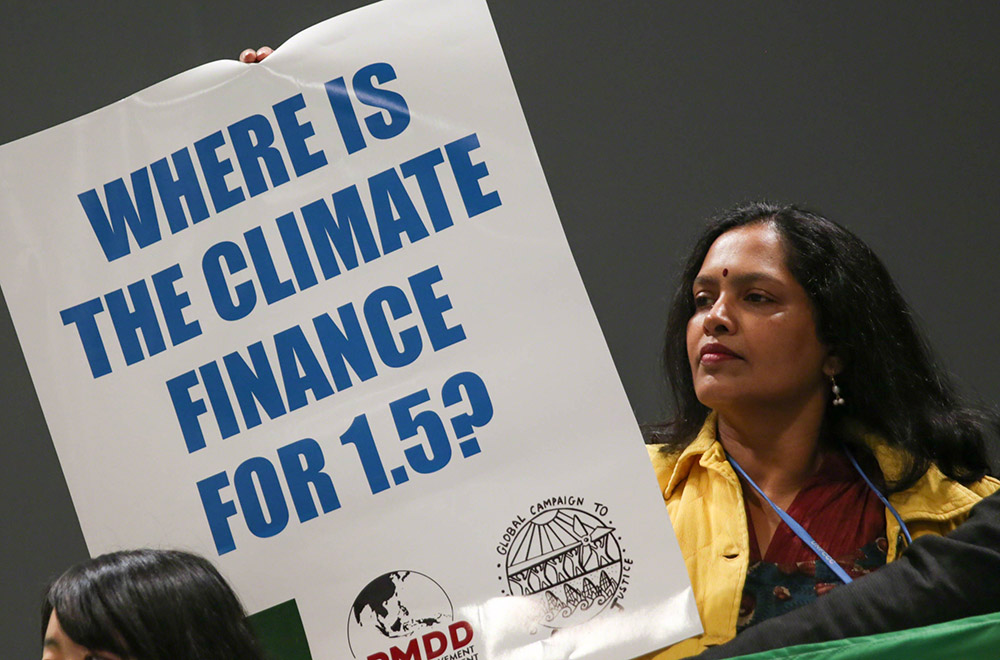

Scaling up finance for

climate action

In 2009, rich countries agreed to deliver $100 billion per year by 2020 by way of climate finance for developing countries. They did so in recognition of their undeniable and overwhelming share of historical pollution. The figure of $100 billion was politically derived and pales in comparison to the real needs which developing countries have to cope with climate change while developing sustainably. The UNFCCC itself estimates that developing countries would require $6 trillion by 2030 in order to be able to deliver less than half of their conditionally pledged climate action under the Paris Agreement.

Every COP since 2009 has reiterated the $100 billion/year goal, but over time the language has been watered down. Developed countries have changed the wording from “deliver” to “mobilise” and then “leverage.” These words sound synonymous but are not and the devil is always in the details. Loans (instead of grants) can result in compounding the injustice of the debt crisis faced by many developing countries. Academics and activists, as well as developing country delegates, have contested the methodology used by rich countries to demonstrate their progress towards this goal as it mostly includes loans, private finance and export credits – as well as funds for other development projects. Oxfam estimates that the true total for public climate finance in the 2017-2018 period was only $19 – 22.5 billion/year.

The Paris Agreement extended the insufficient $100 billion/year by 2020 goal for a further 5 years to 2025. But countries have not agreed on a future goal beyond that. At COP24 in Katowice they agreed to begin a process to set a new collective goal greater than $100 billion/year. In June they discussed the matter in a workshop and in Glasgow will consider the report from that workshop as well as discuss the “effectiveness” and “provision” of finance – how much money is flowing and what good it’s doing. However, developed countries are against talking about long-term finance and resist any attempt to assess their adequacy of their finance contributions, actually proposing to bring the long-term finance work programme to a close. They are also reluctant to honour the commitments they made in Article 9.5 of the Paris Agreement, to report and communicate in advance (ex-ante), indicative quantitative and qualitative information on the finance they will give to developing countries, including projected levels of public financial resources.

Developing countries have long stressed that their finance needs are far from being met from any source and that adaptation is chronically under-funded while there is simply no money for loss and damage at all. With things as they stand, they cannot fully implement their climate actions. The aforementioned UN assessment on countries’ current NDCs relies on full implementation by all developing countries. Without the needs of developing countries being met, temperatures will rise by at least 2.7C. In order to build trust at COP26, rich countries must agree to an operational definition of climate finance. They must also show developing countries that they will scale up these essential funds and commit to deliver the $2.5 trillion/year which UNCTAD estimates is needed for the coming decade. The sources of much needed public finance could be expanded by using mechanisms such as a climate damages tax, air passenger levy, or shifting fossil fuel subsidies.

Stumping up the cash is not a nice thing that rich countries do. It is their moral and legal obligation. By blurring the lines between themselves and developing countries, rich countries are trying to escape this responsibility. They would like to hide the fact that they are rich because of centuries of plunder and pollution. And they would like for poor countries to pay for the climate crisis despite not causing it.

Cooperative approaches to climate action

Since the early years of the UNFCCC, governments responsible for needing to make the deepest emissions cuts have repeatedly attempted to divert this responsibility. They have done so in several faulty and flawed ways: by creating and advocating for “market mechanisms” to trade units of carbon that allow the elite to keep polluting, by incorporating unproven carbon capture technologies into emissions reductions plans, and by advocating for “techno-fixes” including dangerous and untested geoengineering technologies.

The underlying feature of all of these is the principle of offsetting – outsourcing emissions to elsewhere (usually the Global South) or trading credits to buy permission to emit (usually the Global North). Offsetting emissions through market mechanisms is the antithesis to a true climate response from the global community, and from industrialized countries in particular. The science is clear: keeping warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius will require strong emissions cuts, beginning in the developed world, which needs to achieve actual zero emissions as soon as possible. Mechanisms that rely on offsetting delay meaningful action and don’t address the fundamental gap between the 1.5 degree target and countries’ weak progress in emissions reductions.

Furthermore, these mechanisms are rife with loopholes and often allow polluters to increase their emissions and profit from participating in such schemes, all while claiming the false banner of climate leadership. Meanwhile communities and countries in the South are left to shoulder the additional burden of doing the work those historically most responsible should be doing. Previous offset mechanisms under the UNFCCC were widely criticised for harming local people and violating human rights, especially the rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as failing to actually cut emissions. More recently, so-called ‘Nature Based Solutions’ have formed the battleground in the fight to extend the concept of commodification of carbon to all ecosystems, with soil carbon, biodiversity and other values being measured and commodified.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement allows countries to “choose to pursue voluntary cooperation in the implementation of their nationally-determined contributions (NDCs) to allow for higher ambition in their mitigation and adaptation actions and to promote sustainable development and environmental integrity,” and to engage “on a voluntary basis in cooperative approaches that involve the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs)” which can count towards their NDCs so long as they promote sustainable development, avoid double counting and ensure environmental integrity.

The door was thus opened to conflate carbon trading and offsetting with “cooperative approaches” to tackling climate change. The reference to “ITMOs” has also opened the door for the establishment of an international carbon market – contentious given the years of debate on this matter never arriving at an agreement, and laden with pitfalls and risks.

There is no agreement on what exactly are ITMOs and this lack of agreed definition poses the difficult question of what activities and their outcomes a country can use to fulfill its Paris pledge. Can they, for example, be used in the global offsetting scheme under the International Civil Aviation Organisation, known as ‘Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation’ (CORSIA), which is not under the UNFCCC and which could potentially rely on 2.6 billion tonnes of ‘credits’ from supposedly avoided deforestation. Using these credits would potentially allow emissions to increase in addition to the pledged level of a country’s Nationally Determined Contribution. Similarly, can carbon credits from other schemes outside the Paris Agreement also be traded alongside credits generated in the Paris Agreement? Such schemes include the reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation or REDD+ scheme, also highly criticised for leading to increased emissions and harm to forest communities and indigenous peoples.

Rather than focus on more meaningful, equitable methods of cooperation like technology sharing, capacity building, and finance, developed countries especially the European Union insist on setting up a UN-managed carbon market scheme under Article 6.4 that would be compatible with its own regional emissions trading (EU-ETS). If it is established, this mechanism is likely to fail to deliver the emissions reductions outlined in countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement.

Negotiations on the “rulebook” for Article 6 collapsed at both COP24 and COP25, with key sticking points including whether to allow “carryover” of carbon credits generated under a previous market mechanism, how to avoid “double counting” of emissions reductions, how to define project baselines and additionality, how to count the outcomes of activities that cannot be directly measured in greenhouse gases such as geo-engineering projects, whether to include REDD+, and how to ensure environmental integrity and social environmental safeguards including protecting human rights. Market fundamentalists will want to leave Glasgow with detailed technical guidelines to allow them to forge ahead with international carbon markets. Others, notably those who are facing existential threats from climate crisis and who do not stand to profit financially from these market mechanisms, will want principled guidance to try and ensure that if, or when, international markets are established they are strictly regulated and most of all do not increase emissions, nor threaten human rights or environmental integrity. Keeping climate action focused on emissions cuts and phasing out fossil fuels means opposing outright any attempt to negotiate an outcome on carbon markets.

However, Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement does provide an opportunity to address the real drivers of emissions by advancing policies and practices via voluntary cooperation between countries. This could help deliver deep emissions cuts while advancing equity, environmental protection, and well being without relying on carbon markets. For years, outcomes advancing real solutions through Article 6.8 have been stalled in favor of outcomes that have solely focused on trying to agree rules establishing carbon markets under Articles 6.2 and 6.4. At COP26, groups are calling for a decision that swiftly operationalizes the advancement and implementation of real solutions via Article 6.8.

Transparency and timeframes

In addition to the above issues, there are still elements of the ‘Paris rulebook’ to conclude. The Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) is one such issue. The ETF is essentially a set of fairly strict, complex reporting requirements that obliges countries to report on their emissions, their progress towards their NDCs, and the support they have given or received. While the ETF will apply to all Parties of the Paris Agreement, developing countries point out that the differentiated nature of their commitments and capacities mean that there should be both flexibility and enhanced support to help them meet these new requirements. During the June sessions, some developed countries objected to discussions on the provision of enhanced financial, technical and capacity building support for developing countries to cover the cost of ETF requirements. Developing countries found this problematic, especially since developed countries had around 6 years to learn how to comply with reporting rules under the Kyoto Protocol, yet are now telling developing countries to do the same by 2024.

Another as-yet-unresolved aspect of the Paris Agreement is the time frames for subsequent rounds of Nationally Determined Contributions. The first round of these pledges do not apply to the same time frame for all countries and now the debate is whether they should do so in the future. Some countries argue that because the NDCs are nationally determined, the timeframe in which they are enacted should be too. Others believe that without common timeframes it will be more difficult to align national targets with the collective global goals.

Currently negotiations are weighing up four textual options with another eight “proposals” from Parties listed in an annex. Parties will be requested, invited, or required to communicate their next NDC by 2025, and the period it would apply to would be one of four options: every 5 years; every 10 years; “5+5” (Parties would submit two 5-year NDCs every 5 years; or up to Parties to choose between 5 or 10 year time frames. While there is a willingness to reach a decision at COP26 the likelihood is that to progress there needs to be negotiation at a higher political level